The benefits of reflection and role models in learning medicine: An interview with Dr Paquita De Zulueta

1. Comfort, Panic and Learning Medicine

Paquita was thrown into the deep end as a final year medical student, while working as a locum foundation year doctor (“house officer” in those days). On one occasion, she witnessed a death on the operating table and was entrusted with breaking the bad news to the family. She still vividly recalls the neurosurgical operation, which involved the clipping of a berry aneurysm:

“There was an awful moment once he’d opened the skull and put on the clip. It felt as if time was standing still – I felt a sense of impending doom. The clip didn’t quite go around the aneurysm and seconds later there was a surge of blood and that was it. The patient’s pupils became fixed and dilated. She had died. The surgeon threw his instruments on the ground, took off his gown and sat down with his head in his hands.”

Paquita and the Senior Registrar were left to close up the wound. She was later asked to certify the death, which she did not know how to do, as well as break the bad news to the family, for which she had no training. Paquita said the whole experience “made me grow up pretty quickly” and she was grateful for the support she received afterwards.

From my own experience of medical training, there are times when I have felt out of my depth and others where I have been frustrated at not being given responsibility. Being pushed outside of your comfort zone is necessary to progress, both personally and professionally, but it can also increase the risk of making mistakes. In many professions, mistakes may be permissible. In medicine, however, the potential consequences can be high. Ultimately, this means it is even more important to find the balance between support and responsibility.

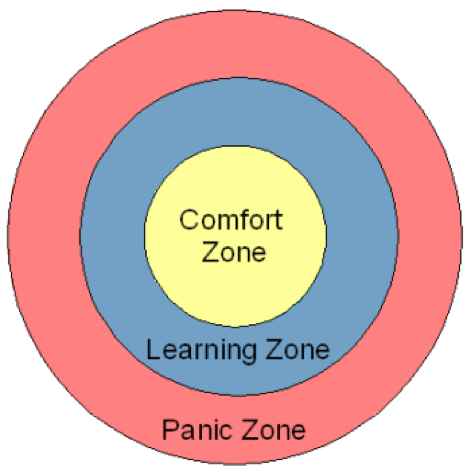

Various theoretical models describe features of the desirable mid-point. Senninger’s Learning Zone Model categorises experiences into three zones; the Comfort Zone, the Panic Zone and an intermediary Learning Zone (Fig. 1). The Learning Zone is optimal, but the other two zones can often be confused for it. Repeated practice of familiar tasks can feel like learning but actually falls in the Comfort Zone and does little to expand skills and abilities. Being thrown into the deep end may feel necessary for learning, but if it is overwhelming and leads to a loss of focus, then it falls into the Panic Zone.

Figure 1: Senninger‘s Learning Zone Model.

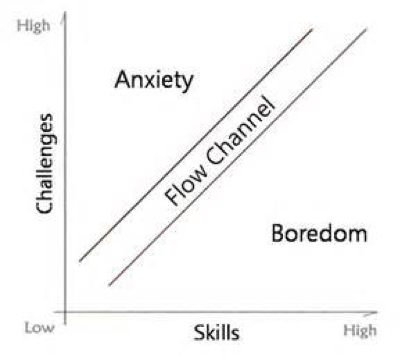

Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of ‘flow’ has significant overlap with this model (Fig. 2). It describes an optimal psychological state, involving immersion and concentrated focus on a task, when a task challenges someone at the right level for their current skill.

Figure 2: “Flow” concept by Csikszentmihalyi.

In an ideal world, we would exert conscious control over the zone that medical professionals experience in their training. While there is scope to do so, the chaotic and unpredictable nature of healthcare can make this challenging.

So perhaps we should look to other ways to increase the benefits or reduce the negative consequences of these experiences. One thing that we can do is maximise the amount the we learn from difficult experiences. Research has shown that one important factor is the opportunity for supported reflection [1]. For some, this type of active reflection can come naturally, but evidence suggests that for the majority it does not [2]. Therefore, there is benefit from fostering an environment where medical students and doctors are encouraged to reflect on their experiences [3].

2. Learning Through Observation

Paquita explained how the most important things she learnt didn’t come from any textbook, but through active observation; of positive and negative role models, as well as of patients.

As a house officer, Paquita worked under Adrian Eddleston, who later became Dean of King’s College School of Medicine. She observed how he combined an excellent questioning style, often getting to the bottom of things very quickly, with a respectful approach that gave patients the freedom to tell their stories. She also found his habit of always looking at patient’s notes before seeing them, and showing an interest and knowledge about their lives, helped to quickly build rapport and facilitate diagnosis.

She advised me: “Find a good role model. Observe them; what is it that they say? What is it that they do? Little things can make a huge difference. Also notice doctors that make you think ‘I never want to be like that’ – What is it that they said and did which had a negative impact on patients?”

Thinking back to me own experiences, I have certainly observed both good and bad practice. Three patterns of modelling have been described in professional socialisation [4]:

– Active identification, where a student likes and copies aspects of a role model

– Active rejection, where a student has strongly different views from the role model and does not want to replicate them

– Inactive orientation, where a student shows no change as a result of interaction with the role model

The spectrum of things that can be learnt through observation is broad. Some of the most obvious influences are on professional behaviours, the development of professional identity, and the shaping of career aspirations [5]. One study showed that observing a competent colleague perform physical examinations led to significant improvement in performance [6].

However, studies have also noted that imitation may perpetuate undesirable practices, such as doctor-centered patient interviewing, and unintended institutional norms, such as discrimination between private and public patients [7]. Simon Sinclair is a psychiatrist and anthropologist who spent a year observing a group of medical students. One thing he noticed was that students, through observation, learnt an aversion to investigating patients’ social and psychological problems [8].

There will be cases where the positive traits of role models that we wish to emulate are obvious. Likewise, there will be traits in strong anti-models that we know we want to avoid. However, there are many traits which fall somewhere between these poles, which I shall term ‘middle models’. It can be easy to assume we are not picking up anything from middle models (i.e. assume inactive orientation) but this may not always be the case. It can be easy to subtly internalise ideals that we may not otherwise consciously choose to adopt in this way.

Our ability to prevent these undesirable traits and attitudes creeping into our practise depends on our levels of awareness. Two levels of self-awareness that have been described are the personal level (where we analyse our own strengths and weaknesses) and the institutional level (where we look at the impact of the institutional culture) [9]. One way in which we can raise self-awareness is active self-reflection.

On the subject of observing patients, Paquita advised the following: “Observe like a detective – you can gain a huge amount from their expression, posture, gait, breathing, and other nonverbal signs. For example, you can pick up a chest problem by noticing uneven breathing or depression by the lowered gaze and the slumped posture.”

3. Reflection

One central idea that my discussion with Paquita highlighted was the benefits of self-awareness and reflection. This may be dismissed all too quickly as a dull topic, but it is one I feel is important. It can be easy to lose the value of reflection in mandatory e-portfolios and compulsory case-based discussions. As we hastily complete the proforma between jobs on the ward, or spend our time ‘reflecting’ the day before a deadline, when we would much rather be doing something else, it can be difficult to conclude anything meaningful. Nevertheless, the reality is that reflection can offer great rewards, whether helping us learn from experiences outside our comfort zones, consciously selecting the traits we pick up from role models or a wide range of other situations.

There are many models of reflection, from Kolb’s [10] to Johns’ [11] to Gibb’s [12] respective models of reflection. I personally like to follow the simple two question approach, asking myself: “what went well?” and “even better if…?” approach (informally known as the ‘WWW and EBI’ tool).

It is easy to get caught up in daily goings-on at work or home, the latest news or happenings on social media. It is also easy to leave it until the last minute to force a ‘reflection’ and tick the necessary boxes. The real benefit comes when reflection becomes a spontaneous and thoughtful habit for no-one’s benefit except our own and the patients we will treat.

4. References

[1] Teunissen, P. W. et al. How residents learn: qualitative evidence for the pivotal role of clinical activities. Med. Educ. 41, 763-770 (2007).

[2] Ertmer, P. A. & Newby, T. J. The expert learner: Strategic, self-regulated, and reflective. Instr. Sci. 24, 1-24 (1996).

[3] Driessen, E., Tartwijk, J. van & Dornan, T. The self critical doctor: helping students become more reflective. BMJ 336, 827-830 (2008).

[4] Shuval, J. & Adler, I. The Role of Models in Professional Socialization. Soc. Sci. Med. Part Med. Psychol. Med. Sociol. 14, 5-14 (1980).

[5] Passi, V. & Johnson, N. The impact of positive doctor role modeling. Med. Teach. 38, 1139-1145 (2016).

[6] St-Onge, C. et al. From See One Do One, to See a Good One Do a Better One: Learning Physical Examination Skills Through Peer Observation. Teach. Learn. Med. 25, 195-200 (2013).

[7] Benbassat, J. Role modeling in medical education: the importance of a reflective imitation. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 89, 550-554 (2014).

[8] Wright, S. Examining what residents look for in their role models. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 71, 290-292 (1996).

[9] Maudsley, R. F. Role models and the learning environment: essential elements in effective medical education. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 76, 432-434 (2001).

[10] Kosir, M. A., Fuller, L., Tyburski, J., Berant, L. & Yu, M. The Kolb learning cycle in American Board of Surgery In-Training Exam remediation: the Accelerated Clinical Education in Surgery course. Am. J. Surg. 196, 657-662 (2008).

[11] Johns, C. Working with Alice: a reflection. Complement. Ther. Nurs. Midwifery 6, 199-203 (2000).

[12] McGregor, D., Cartwright, L. & Vye, D. ‘Reflection, Reflection, Reflection. I’m thinking all the time, why do Ineed a theory or model of reflection?’. in Developing Reflective Practice: A guide for beginning teachers (Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education, 2011).

Article photo credit: https://www.pexels.com/photo/writing-notes-idea-class-7103/

- Log in to post comments